IN 1947 Postwar Tokyo was a city of silence, its populace stunned by massive destruction and despair. Yet a young GI witnessed signs that the people were on a slow mend, ready to rebuild Tokyo and themselves. It was winter – cold, crisp, clear – and Mt. Fuji stood sharp on the horizon, growing purple, then indigo in the fading light. I was standing at the main crossing at Ginza 4-chome.

There was no smoke because there were few factories, no fumes because the few cars were charcoal-burning. Fuji looked much as it had for Hokusai and Hiroshige.

Then the sky darkened and the stars appeared – bright, near. The horizon stayed white in the winter light after the sun had vanished and Fuji had turned a solid black.

The Ginza was illuminated by acetylene torches of the night stalls and the passing headlights of Occupation jeeps and trucks. In the darkness Fuji remained visible, a jagged shadow fading into the winter night.

Most of the buildings were cinders. It was wasteland. And from the crossing Japan’s familiar peak was seen as it had not been seen since Edo times and as it would not be again seen until another catastrophe.

At the crossing there were only two large buildings still standing. One was the Ginza branch of the Mitsukoshi Department Store. But it was gutted, hit by a fire bomb, and even the window frames had been twisted by the heat. Across the street was the white stone Hattori Building with its clock tower. It was much as it had always been, once the clock itself was repaired. With its curved front window, cornices, and pediments, it remained from the pre-war Ginza.

South there was not much, nor east, where the standing ruins of the burnedout Kabukiza constituted the view. West was the round, red, drum-like Nichigeki and the Asahi Building. At Hibiya there were a few buildings, some theaters. There was the Sanshin Building, still standing; the Asahi Seimei Building where the MP offices were, the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater, then called the Ernie Pyle; and the Hibiya and Yurakuza motion picture theaters – these last now destroyed, as has been so much else, by peace, affluence and the high price of land.

The view was block after block of rubble. The wooden buildings had not survived. Those that still stood were made of stone or brick. Yet, already, among these large, fire-blackened structures, there was the yellow sheen of new wood. Reconstruction was under way. It was the first month of 1947, over a year after the end of the Pacific War.

People were still returning to the city. During its destruction many had left and now it seemed that every day more returned.

During my cold late-afternoon Ginza stroll, walking down to view Fuji in the five-thirty twilight of mid-winter, I saw numerous people shuffling along the pavements. But there was no laughter and little conversation. One somehow expected festivity – there were so many people shambling along or lounging about. But there was none. And instead of shop windows there were the street stalls, each illuminated by its gas torch.

Everything was being sold – the products of a dead civilization. There were wartime medals and egret feather tiaras and top hats and beaded handbags. There were bridles and bits and damascene cufflinks. There were ancient brocades and pieces of calligraphy, battered woodblock prints and old framed photographs. Everything was for sale - or for barter.

And around the stalls, the people. Uniforms were still everywhere – black student uniforms, army uniforms; young men wearing forage caps, or their army boots, or their winter-issue overcoats. Others were in padded kimono, draped with scarves. Women still wore kimono or wore the mompe trousers used for farm work which in the cities constituted something like wartime dress. And many wore face-masks because of winter colds. And everyone was out of fashion. In peacetime they were still dressed for war.

The crowd was very quiet. The only sound was the scuffling of boots, shoes, wooden sandals. That and the noises of the merchandise being picked up, turned over and put down. The merchants made no attempt to sell. They sat and looked, perhaps smoking a pinch of tobacco in a long-stemmed brass pipe, staring at the black throng passing in the darkness of an early evening.

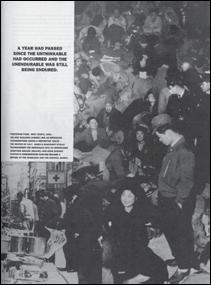

When I remember faces I cannot remember anyone talking. I remember the quiet and the glances. A year had passed since the unthinkable had occurred and the unendurable was still being endured, and I saw a populace yet in shock.There was an uncomprehending look in the eyes. It was a look one sometimes still sees in the eyes of children or the very ill.

And in the eyes of convalescents as well. People recuperating are people keeping quiet. Yet, compared to the clatter and chatter of 44 years later – today – Tokyo was a city of the dead. So many had been killed in the city – so many had been burned or boiled in the fire-bomb raids of 1945. The survivors remembered.

But at the same time the dead were being forgotten, as they must be if we are to go on living. Every day the crowds got larger, the eyes grew brighter.

I remember a small newsstand on the Ginza run by a tough, smiling country woman. An army helmet was displayed and under it was a similar-looking pot. The sign said: We Will Turn Your Old Helmet Into a New Cooking Pot for Only Seven Yen. I still have a photograph taken earlier in the subway corridors of Ueno Station. There, sitting or lying down, are some of the thousands of the hungry homeless. Men, women, a few children, on straw matting or on the bare concrete.

They are being inspected by two bespectacled policemen wearing mouth-masks. Many of the people are dirty, and all wear remnants of what they had owned during the war: cracked shoes, torn blouses, buttonless shirts, battered hats. The most surprising thing about the picture, however, is that it is not sad.

Everyone in it is smiling – everyone except the policeman, and maybe they are as well beneath their masks. Smile for the camera, make a good impression, best foot forward. Even in the depths of national poverty everyone remembered this.

Up above, on the plaza-terrace, around the statue of Takamori Saigo, there were many more, sitting on benches and embankments, some with a newspaper, some with nothing at all, all of them waiting. Waiting, it seemed, for this too to pass so that they could get on with their lives. They were like people in a train station.

The crowd had killed the grass by sitting, squatting, lying on it over the weeks and the months. And many had been and gone. The pedestal of Saigo’s statue was plastered with hand-printed notices: Watanabe Noriko – Your Mother Waits Here Every Day from One to Five; Grandmother Kumagai – Shiro and Tesuko Have Gone to Uncle Sato’s in Aomori – Please Come; Suzuki Tetsuro – Your Father is Sitting on the Staircase to the Left – If You See This Please Come.

The rains and the snows washed them away and new ones were put up. They were like the votive messages left at shrines invoking supernatural aid. Answered or not, they were left there until rained away or covered by notices of later misfortunes.

Tokyo back then was poor. Poverty gave it the Asian look, an appearance which prewar Japan had been at some pains to avoid. But then Asia had moved closer. And with it a kind of natural nudity.

In summer, a part of the populace was near naked. There were no more laws against going naked and so people naturally did – being naked is more comfortable than being clothed.

I used to stand on the street corners – not perhaps those of Ginza, but certainly those of Ueno and Asakusa – and gaze at the shapely limbs, the proud bearings, the curves and angles of all this beautiful bare skin. And some not so beautiful to be sure. Malnutrition is no beauty aid.

When people are naked, one of two things can occur. The viewer can become excited, feel sexy and tend to view the nude as an object of desire. Or, this same viewer may view the human race, finally as it is – innocent, vulnerable, unknowing, and beautiful in that general way which insists upon the humanity of each person.

Standing on the corner I felt both, alternately, depending upon how I had slept, what had happened that day, even, for all I know, what I had eaten. But only one at a time. One cannot experience such disparates simultaneously.

I remember Tokyo moving slowly in front of me, fittingly and suitably undressed in the hot summer night, showing a beauty and innocence and a naturalness which allowed me to say to myself: “Ah, this is Asia.” By then the rickshaws were gone but the pedicabs, bicycled rickshaws introduced late into Japan, were not. These were like large tricycles. In front was a man or boy astride his bike. At the back was the twowheeled double seat in which one reclined while being pedaled about.

They were much more commonly seen than taxis, though the taxis were more noticeable. This was because they all carried large round tanks at the rear that in the cold of winter emitted clouds of smoke and steam.

These taxis were running on charcoal. The arrangement was apparently complicated and needed much stoking. They never went very fast and were much given to breakdowns.

There were buses, some of these also charcoal- run, and after electricity was again general in the city, streetcars. There was also a variety of buggies – a few horses but more oxen. I remember seeing braces of oxen on the Ginza.

From early on, a number of attempts were made to keep occupiers and occupied apart. They were not to be allowed in the same place. We were so informed: No Fraternization with the Indigenous Personnel – this is what the signs said.

broad white stripes painted on their sides. From one of these, seated in comfort, we would see into the other cars and look at the people crammed flat against the glass. The subway (there was only one line – Shibuya to Asakusa) was off-limits to The Legacy of Donald Richie Occupation personnel, as were the buses. Only the streetcars were, for some reason, allowed. There, occupiers and occupied were permitted to promiscuously mingle.

Occupiers also could not eat in any of the restaurants still operating in those days of foodrationing. Nor could they go to any of the local entertainments. No movie theaters, no all-girl dance shows – much less the Kabuki, showing at one of the department store theaters until its own home was to be rebuilt. Instead, there were special nights when the occupiers, and only the occupiers, were invited. Thus, one by one, we got to see the Noh, the Bunraku, the Kabuki, the Takarazuka All-Girl Opera, the Kokusai Gekijo All-Girl Dance Team, and other examples of Japanese culture.

The effect of such segregation was to make one want to flaunt integration. And this we all did, though penalties were enforced. For Japanese who tried to enter forbidden occupied zones the punishment was extreme: they were handed over to zealous Japanese police, anxious to placate outraged Occupation authorities. For the occupiers caught in a bar or all-girl opera or Kabuki, the penalty was severe enough. The culprit received a D.R. (Delinquency Report) and if he had acquired a certain number of these he was, it was said, sent home.

Nonetheless, the occupiers nightly flocked where they were not supposed to. The most popular of these off-limit places were not the theaters but the brothel districts. These were, discreetly, just everywhere. The largest, most famous, most lucrative was out of town, in Funabashi, which you had to have a jeep or a truck to reach – two houses, side by side – one for officers, the other for enlisted men. Here the MPs were never seen, except, of course, as customers.

Another place where fraternization was permitted was the Mimatsu Night Club, a large building directly behind Mitsukoshi Department Store on the Ginza. In the afternoon the occupied went; in the evening, the occupiers. At five the doors were closed and the Japanese customers were turned out; at six the doors opened and the Allied customers were ushered in. At nine the doors closed for good.

Dancing was permitted. That was the extent of it. MPs patrolled the premises. Under orders from a General Swing they also carried with them a rule just six inches long. This they would from time to time insert between the bodies of a dancing GI and his indigenous partner to make certain that fraternization was not taking place. Shortly, however, this petty custom was laughed out of existence.

The six-inch rule did not apply when the GI went to Yurakucho Station directly behind the Dai-Ichi Building – GHQ Headquarters – and there took his pick of all that was parading up and down. I remember the whores’ uniform well because it was so fetching.

The girls wore dirndl skirts, then a minor rage in the U.S., with limp cotton tops and lots of wooden jewelry, bracelets and necklaces and the like, all machine-tooled and painted a cherry red. The hair was piled up or else frizzled in the popular “cannibal” fashion of the day. On the feet were platform shoes with cork soles, and silk stockings were often painted on – using very strong tea – with a perfectly drawn back seam on each leg.

The proper present was a pair of real silk stockings, straight from the PX. But equally welcome was food from the commissary – cocktail sausages, canned stew, Ritz crackers and for, the truly adventurous, Kraft Velveeta.

Goods were safer than money and though the PX and Commissary rationed some items, most of us could buy what we wanted. There were, for example, no ration rules on Almond Crunches, a favorite confection of my Japanese friends.

Many, though not, I trust, my friends, sold their goods. Particularly popular were American cigarettes and whiskey, lighterflints, and Spam. All became symbols of status among the Japanese – until they became common enough that everyone had them. Lighting a Lucky was like driving a Rolls.

How rich we were. And how poor they were. So, now when I see foreign youngsters, much the same age as those GI conquerors, and I watch them teaching English or, better, working as waiters and doormen at expensive bars and clubs, I realize that all is well with the world. What goes up must come down; what is taken away is, eventually given back. The people of Tokyo, some of them at any rate, are now as rich as they were once poor. tj

|

|

|

|

||

The complete article is available in Issue #271. Click here to order from Amazon