DONALD RICHIE An Appreciation

by Peter Grilli

Written for the Memorial Gathering at International House of Japan, Tokyo (April 15, 2013)

AS the world mourns “Donald Richie, the writer,” “Donald Richie, the renowned expert on Japanese cinema” and “Donald Richie, the insightful commentator on Japan,” I stand in awe of the deluge of affection and gratitude that has greeted the news of his death. One might well expect such a response from the community of specialists on film history or on Japan, the critics, historians and academic experts who had benefited for decades from his work. It could be no less, after all, since Richie had written so extensively on those subjects and is counted among the iconic giants of these fields of study. But the tributes, letters, essays, e-mails, blogs and tweets flowing from countless admirers who had never met him or heard him speak – people who knew him only from his writings – is nothing less than astonishing. “He changed my life” or “he opened my eyes to new worlds” are common themes. Or “he showed me how to see.”

Donald changed my own life in many ways... and, indeed, he showed me how to see. He has been a direct and continual influence on me since childhood, and I know he will remain so for the rest of my life. In every person’s life there are certain individuals – apart from the parents responsible for one’s very existence – who teach or shape or inspire, who mold or influence one’s consciousness in fundamental ways. Donald Richie was such a one for me: a mentor, a teacher, a role model, a friend, a beloved “uncle” unrelated by blood. I will always be in his debt.

He entered my life around 1949 or 1950, as a friend of my parents. I immediately claimed him as a friend of my own. I was about eight at the time, a child of no understanding and little expectation of the special role this friend would play in my life. Donald was 25 or 26, far younger than most of my parents’ friends and somehow different. He paid closer attention to me and my younger sister than most of the others and he never patronized or spoke baby-talk to us. He was a writer, I was told, though at the time I didn’t really know what that meant. And he laughed a lot – something I could understand. At the time, Donald and my parents and many of their friends were part of something called “the American Occupation of Japan,” and I didn’t know what that meant either. My parents had many friends, some American and many more Japanese. Certain distinctions soon became clear to me: the Americans were members of “the Occupation;” the Japanese were not. Nor were the Europeans or Chinese or Australians, who also visited my home from time to time. I was delighted that Donald came more often than most of the others; he was more fun. Sometimes he came alone, often on Sunday afternoons, and that was the best of all. He would read to my sister and me, speak with us as equals, and devise intriguing (and often baffling) word games. From Donald I learned, early on and unconsciously, the value of words.

Occasionally, my mother and one or two other friends would join in the Sunday afternoon amusements, which sometimes involved dramatic readings of a play. Often it was rather simple fare: Our Town, for example, or The Diary of Anne Frank. But sometimes we took on tougher challenges. One unforgettable Sunday when I was nine or ten and deemed “ready for Shakespeare,” it was The Tempest. Each of us took several parts, and Donald – as was his custom – got all the best roles. Imagine Donald Richie as both Prospero and Caliban in a single afternoon! My mother was Miranda, and I was assigned the roles of various rough sailors and island creatures. That was the kind of “uncle” that Donald was: imaginative, inspiring, utterly uninhibited, colorful and unforgettable. I looked forward to those dramatic Sunday afternoons, and wished they happened more often.Whenever Donald came to the house, I wanted the day to go on forever. Today, as I read the comments and blogs that flood in from around the world, I find myself responding instinctively to those anonymous admirers of Donald’s who write that he “helped me learn to see…”

I knew nothing then of Donald’s life outside our living room. I had no notion of what his occupation in “The Occupation” might be or who his friends outside our living room were. None of that mattered to me then. He was my mercurial “Uncle Donald,” who existed only to enrich the world of my imagination. Later, I would learn the facts and would begin to put together the pieces that formed the mosaic that was Donald Richie. Later, I would read his books and come to know his various circles of friends. Later, I would attend musical evenings or “happenings” that he conceived and produced. Later, I even had a bit part in one of his mystifying films. Later, I joined him occasionally on film-festival juries. Much later, I even arranged lecture tours for him and watched with delight as he was applauded for his unique knowledge and insights about Japanese film history. But back then, on those wonderful Sunday afternoons, I knew none of the facts. I knew only the magic that my “Uncle Donald” brought into my life.

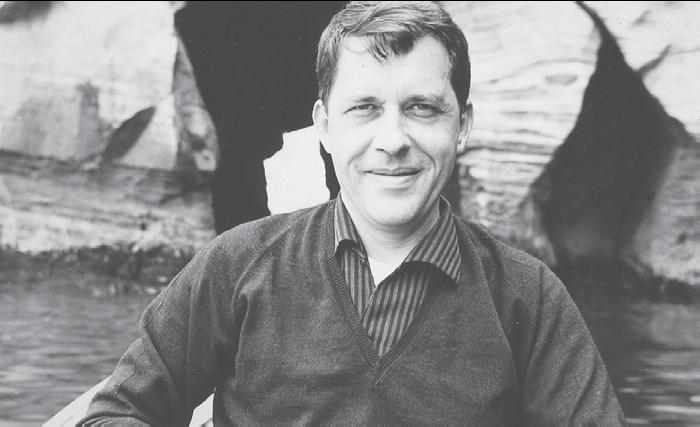

He was from Lima, Ohio, born there in 1924, a town from which he fled within days of graduating from high school. He lived most of his life in Japan, a country that was not his own but which he observed closely for more than six decades and described in infinite detail. In conversations late in life he loved to speak of himself as a “flaneur,” a passionate spectator strolling along the boulevards of life, appreciating everything he saw but participating only occasionally, savoring the nuances but not causing or directing any of them. In Japan, especially, he relished his role as observer: “I think one of the joys of being an expatriate is the complete freedom that it gives you…” he commented in a Pinewood Dialogue of 2006 “…particularly in Japan, where foreigners are held in a separate box, as it were, a separate category, where what applies to the Japanese does not necessarily apply to the foreigners. And so this specialness gives you a kind of a freedom. It doesn’t give you license. It doesn’t mean you can just do anything you like then. But it makes you aware, in a very strange kind of way. And it prevents your having any of the comforts of belonging to any category… I’m, like, on the mountaintop, where I can look back to the plains of the snowbound province of Ohio, where I came from. And it doesn’t have any hold on me. It doesn’t form me. It has formed me, but it doesn’t have anything to do with my life right now. I can look down at the sunny valley of Japan, the land I’ve chosen, and know that I can never go down there. I look at it and I take strolls, but I’m never going to belong to it, or it to me. And so this gives me, all of a sudden, a kind of freedom I didn’t have before. I become a citizen of limbo. And limbo is the most democratic state there is.”

He came to Japan in 1947 as a lowly staff member of the Tokyo branch of the Stars and Stripes, the American military newspaper. He was initially a typist, transcribing the words of others, but soon Donald began writing pieces of his own; his first published articles on Japan were human-interest stories, and by October 1947 he was identified as a “feature writer.” Later on, he began writing movie reviews for The Japan Times. As a budding filmmaker himself, he visited film locations and studios, slipping comfortably into the community of Japanese directors, actors, and filmmakers whose work he found interesting and stimulating. Still later, he added book reviews to the Japan Times movie columns, and eventually original essays and commentaries about Japanese life as he saw it. His obsession with Japan persisted for more than sixty years, and his observations and insights about his adopted home fill nearly fifty books and spread out over countless essays, lectures, interviews and published interviews or dialogues. Like Lafcadio Hearn, a writer whom he admired and emulated, he wrote about Japan from direct personal experience. Continuously on the ground, living the life, writing as both a journalist and as a poet, Donald’s journals and his more formal writings provide an unrivalled portrait of Japan in the latter half of the 20th century. His early novels grew out of his personal experience of Japan, and excerpts from his journals of travels in Western Japan were refined and coaxed into a book called The Inland Sea, published in 1970. Far transcending the usual travel genre, it is a profound meditation on Japan. It is his masterpiece.

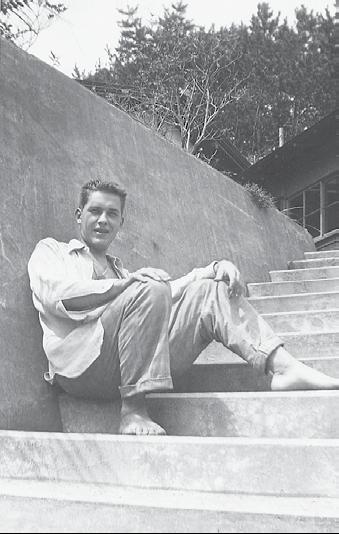

| 1 — At Engakuji, Kamkura, 1947. © Eugene Langston | 2 — In Nakano, Tokyo, 1948. © Holloway Brown | |

|

|

|

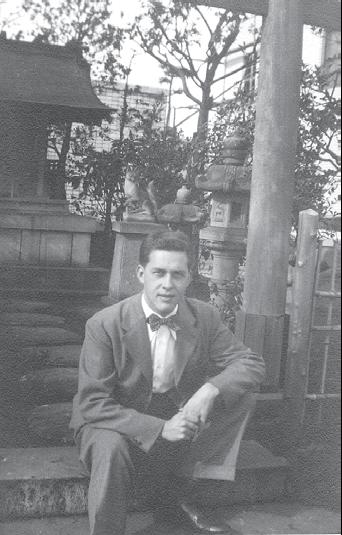

| 3 — At a rooftop shrine, Ginza, Tokyo, 1948. | 4 — The Inland Sea (first edition; Weatherhill, 1971) | |

|

|

As we all know, Donald loved films, all films – Japanese, American, European, Indian, Korean, Iranian – and, regardless of their source, he wrote about them as a critic, as a The Legacy of Donald Richie 1 2 scholar, and most importantly as a fan. But what is perhaps less well known is that he was himself a filmmaker. He made his first film at seventeen – an 8mm meditation on Lima citizens going in and out of churches called Small Town Sunday – and later on, in Japan, he directed nearly thirty more experimental pieces (ranging in length from 5 to 47 minutes), six of which have been collected and distributed on DVD. He was also an avid painter and occasional print maker. This is, to me, the key to understanding the perceptiveness of this insightful man and the unique flavor of his descriptive writing. His genius was as much that of a visual artist as of a literary one: seeing and setting down what he saw in a visual vocabulary. “Film seeing” is different, of course, from ordinary looking around because it requires the decision-making talents of an artist. “Film seeing” is not random; it involves infinitesimal choices: where to place the camera, how to manage the lighting and to set the lens aperture, how long to roll the film, how to edit the shots, and how – ultimately – to control the perceptions of the film viewer. That is how Donald wrote: with the eyes of a movie-maker.

Donald’s life in the movies began early in his childhood, and he watched movies throughout the 88 years of his life. Television he hated for its reduction of the eyes and the mind of the viewer. The night before he died, he watched a movie on DVD. “The movies” he wrote in 2006, “were sort of the thing we did when we were little. Particularly me, because I was very often—when I was three or four— sent to the movies, to be kept quiet. And I would sit there mesmerized. I had no idea what was coming next or who they were or what they were doing. The fact that it was moving was enough. So I became sort of a charter member of the movie generation, and went to see everything that played in this little town where I was born. The movies became my reality. The people I saw became more real than my family. Johnny Weissmuller was a lot more real than my father was. And when Norma Shearer wept, I cried along—as I never did when my mother cried. And so, movies became my preferred reality… This continued on, and then one day, I finally discovered what movies were doing. I walked into the Sigma Theater in Lima, Ohio—and I again paid no attention to what was on the marquee at all. (I never looked at what was playing; it wasn’t important.) As soon as I went in that day I thought, ‘Something’s the matter; the projectionist is probably drunk again,’ because it first started with the end of the picture: the old man in the bed died. And then all of a sudden came the newsreel. And then after that it picked up, and it kept jumping back and forth. And I was certain that the reels were utterly mixed up, until it all began to make a kind of sense. And by the end of the film, I knew what film was, and I almost knew what life was. The film was Citizen Kane. And this inspired me so much. Up to that moment, I had been only a passive observer of movies; now I wanted to be active… I was enthused, you know, living through film— but consciously this time. That was the beginning, and that has continued now for eighty-two years. And this is the way that I am.”

How lucky we are that Donald Richie lived so long in Japan and how specially fortunate that he wrote with the mind of a filmmaker. When admirers today say “he helped me see…” there is true meaning in those words. Donald knew all the great Japanese film directors of what has been called “The Golden Age of Japanese Cinema” and he responded intuitively to their genius. When he watched them on location he needed no explanations to understand what they were about. When he interviewed them, he understood their words almost without needing language. When he viewed their completed films and wrote about them he could convey their meanings with the insight of a fellow artist. And, ultimately, when he observed and commented on their observations and commentaries on their own society his writings were informed by the unique consciousness of the flaneur.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is still too soon to calculate the full extent of Donald’s contribution to the world’s understanding of Japan. That it is enormous is without question. The sheer quantity of his works is staggering, and time will filter the enduring classics like The Inland Sea, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (co-authored by Joe Anderson), The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Ozu: His Life and Films, Different People: Pictures of Some Japanese (also published with the variant titles Japanese Portraits: Pictures of Different People and as Geisha, Gangster, Neighbor, Nun: Scenes from Japanese Lives) from his more casual essays or more quotidien newspaper reviews of films or books. I am willing to bet that some of his books — A Taste of Japan or A Lateral View: Essays on Culture and Style in Contemporary Japan or Tokyo Megacity, to give only a few examples – will become increasingly important to future readers. Books like The Donald Richie Reader and The Japan Journals, 1947-2004 will command positions of permanent value to anyone seriously interested in 20thcentury Japan.

Earlier, in referring to Donald’s “more casual essays,” I meant only to suggest that they can be read with ease. There was nothing casual about Donald’s experience of Japan or his writing about it. He was a serious and fully committed writer, who struggled mightily with his subject and worked hard at the craft of elucidating Japan. Like any dedicated writer, he worked at his desk for hours each day before allowing himself the pleasures of travel or strolling the streets of Tokyo. Going to movies was, of course, an endlessly renewing pleasure for him, but he watched them with professional attention, sighing with joy at a masterpiece but also moaning at the clumsy imperfections of the lesser films he had to watch. Sophisticated though he was in his lifelong experience of movies, he always seemed to enter a theater with an almost childlike optimism, hoping eagerly to discover some unexpected jewel in the film he was about to see.

As Donald’s years of residence in Tokyo lengthened and as his fame expanded, he became the person to go to for all of the world’s journalists, writers, filmmakers, artists and intellectuals visiting Japan for the first time. Generous with his time, he accommodated nearly all of them, especially when they came well recommended or preceded by their own esteemed reputations. Visitors as varied as David Riesman, Susan Sontag, John Cage, Stephen Spender, Maurice Bejart, Jim Jarmusch, David Halberstam, Claude Levi-Stauss, Francis and Sophia Coppola all came to know Donald well and it was under his tutelage that they encountered Japan. He was a wise teacher, never forcing his own views on such visitors but gently guiding their perceptions and enabling them to “see” with informed eyes. For this alone, apart from all his other contributions, Donald Richie deserves a hallowed place in the annals of international cultural exchange

His books are read and cherished all over the world. But one important audience still awaits full exposure to the insights of Donald Richie’s writing about Japan: the Japanese themselves. To me this has always seemed rather odd, since sophisticated Japanese people tend in general to be acutely conscious of what the rest of the world thinks or says or writes about Japan. Though several of Donald’s film books have been translated into Japanese, most of his non-film books have not. In time, I hope, Japanese readers will come to discover his works. Shortly after his death, I was profoundly moved by a comment of one Japanese friend who had taken the trouble to read many of Donald’s books in English: “How much we need him! I hope all of his books will be translated into Japanese so we can learn more about ourselves from this wonderful American writer who loved us so much!” tj

| 5 — At Nikkatsu Film Studio, in front of a miniature set, 1956. © Nikkatsu | 6 — At Dogashima, 1964. © Mary Richie | |

|

|

The complete article is available in Issue #271. Click here to order from Amazon