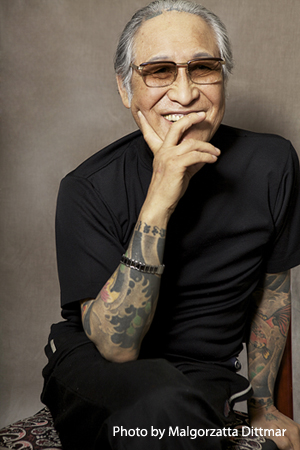

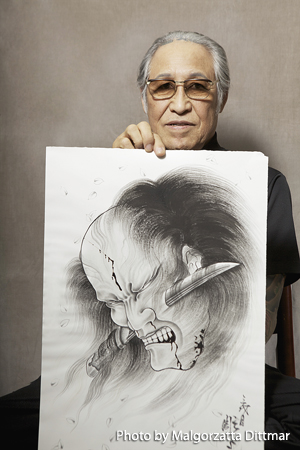

Horiyoshi III

Japan’s Legendary Tattoo Master

Interview by Kimo Friese and Horikichi

TJ: Can you introduce yourself to our readers?

TJ: Can you introduce yourself to our readers?

HORIYOSHI: My real name is Yoshihito Nakano. I was born on March 9, 1946 in Shimada, Shizuoka. I am the eldest son with a sister and brother.

TJ: Tell us a little about Irezumi, the traditional art form of Japanese tattooing.

HORIYOSHI: It depends what you mean by traditional? Tattoo tradition, Japanese tradition or Asian tradition? If you say Asian tradition, it was most affected by Confucianism. But if you are obedient to Confucianism, you can’t get tattooed because the belief states that you should not hurt your body. But since tattoo culture had already existed before the ancient Chinese ideas that transformed into Samurai philosophy in Japan, Confucianism couldn’t exclude tattoo culture. The concept of the tattoo can translate into strength, religion, or many other things. But in Japan, it basically represents courage or strength, like the Samurai’s fighting spirit. On the other hand, tattoos also have artistic aspects. Actually, it’s difficult to talk about Irezumi tattoo and tradition because the scope is too wide.

TJ: Is there a commonalty between Confucianism and the art of tattooing?

TJ: Is there a commonalty between Confucianism and the art of tattooing?

HORIYOSHI: Nothing in common. Tattoos are completely contrary to the idea of Confucianism. It doesn’t allow for the hurting of the human body.

TJ: What about Buddhism?

HORIYOSHI: Buddhism doesn’t deny tattoos. According to Genkō Shakusho, a book on Buddhism from the Kamakura era, there was a priest with a tattoo of the Buddha who lectured throughout Japan. Buddhism neither encourages nor denies the Irezumi tradition.

TJ: Some Japanese embrace Buddhism-related Irezumi. What’s your feeling on that?

HORIYOSHI: Frankly speaking, many see it as just a design and not a sign of faith. For example, when someone chooses Cetaka as a tattoo design they often say, “I don’t know what it is, but it is cool.” That’s fine. If they realize later on what it represents it doesn’t matter because there are no malevolent Buddhism-related designs. Even a demon can be relied upon if you make a friend of him. After all, Buddhist images are a human creation.

TJ: How did you get into tattooing by hand?

HORIYOSHI: When I started tattooing, very few machines were available. Nowadays, using machines is the norm. So tattooing by hand was the way for me to get started. I decided to apprentice under Horiyoshi because I liked his work.

TJ: When did you become interested in the Irezumi tradition?

TJ: When did you become interested in the Irezumi tradition?

HORIYOSHI: Probably around the age of 10. I saw a man with Irezumi tattoo work in a sento, or public bath. I was overwhelmed. That evening I talked with my family at the dinner table about Irezumi tattoos. My father and grandfather told me a lot, like the fact that my great-grandfather had Saraswati on his back. That was so impressive. In the second grade I was drawn to a library book, Bunshin Hyakushi, which was full of Irezumi pictures. I got deeply into it. By the age of 15, I got a small Irezumi on my foot. An older kid saw it and asked me to do one on him. It was my first experience of tattooing. I was 15 or 16 years old. I gradually gained customers by word of mouth and started to earn a living. At that time there was no information about the mechanics of tattooing, so I learned through trial and error. At the age of 21 I was tattooed by Horiyoshi and continued to develop my own style of tattooing. At the age of 25, I began an apprenticeship to broaden my technique. I wrote to Horiyoshi, but I got no reply. Next, I sent strawberries with a letter, but again, no reply. So I visited Horiyoshi and asked him directly. At that time, Horiyoshi II was absent, so I met with Horiyoshi I. He said I couldn’t earn money while apprenticing, but I insisted on learning anyway. I was finally accepted. After a few months, I started apprenticing. Horiyoshi II came home and said, “Had I been here when you visited, I would not have accepted you.” Timing is really important in life; some things are just meant to be and are beyond our control.

TJ: What were your options then, had you not been accepted as an apprentice?

TJ: What were your options then, had you not been accepted as an apprentice?

HORIYOSHI: If I was rejected after staying for three days in front of the gate, I was going to ask him to introduce me to the Yakuza in Yokohama. I was determined not to give up, but I did think of joining the Yakuza had I been rejected. I was 25 years old at that time.

TJ: When were you given the title “Horiyoshi III?”

HORIYOSHI: Probably in 1979.

TJ: What are some of the fundamental differences between Japanese Irezumi tattoo and the Western tattoo?

HORIYOSHI: There used to be apparent differences, but not so much now. Japanese Irezumi uses the body as a canvas to relate a story. Western tattooing draws on small, individual images. Japanese Irezumi incorporates narrative imagery: seasons, flowers, mountains, water, rocks and so on are important. It’s all part of the bigger picture.

TJ: What do you think about the interest in Japanese Irezumi outside of Japan?

TJ: What do you think about the interest in Japanese Irezumi outside of Japan?

HORIYOSHI: The human body is beautiful. I think Japanese Irezumi has beauty of form that explores the human body. In the West, people have become interested in the beauty of form in Japanese Irezumi. It has rules and sophistication. It’s not surprising that Japanese Irezumi is accepted worldwide. Foreigners are starting to understand the beauty of it.

TJ: Any advice for those getting tattooed for the first time?

HORIYOSHI: First of all... no regrets. Think it through thoroughly and know your design well. People often prefer getting tattooed in visible areas on the body, but it’s cool to get them where they will be covered up. Tokyo Journal #274 Tokyo Journal #274 26 27 As a tattoo artist, I think that is preferred. Tattoos are not meant for exhibition.

TJ: Are there many people who give up while getting tattooed?

HORIYOSHI: There have been many. I remember one man quit in less than five minutes, saying “I forgot to turn off the gas, so I have to go home.” Another man said, “What day is today? I forgot an appointment. I have to go!” even though he made an appointment with me on that same day. They don’t want to be shamed by saying, “I want to quit because it’s painful.”

TJ: What was your first experience like when you used a machine to tattoo?

HORIYOSHI: The first machine I used was sent to me from a man I had met at a tattoo convention in Rome. I struggled with it for a while before finally managing to handle it. My first impression was: “It doesn’t work well.” After that I bought some machines, but they didn’t work well either. I managed to use one of them, and sent out pictures of my work. The machines didn’t come with “manuals,” so it was difficult. At the age of 24, I made a tattoo machine using an electric razor. It moved very fast and powerfully. Horiyoshi I still worked by hand and Horiyoshi II had started using a machine. I stayed away from machines because I thought the hand method was much faster. But I was shocked and changed my mind when in 1985 I met experienced tattooists using a machine in Rome. I was keenly aware of the necessity of accepting Western tattoo culture at that time.

TJ: How long did it take to master machine tattooing?

HORIYOSHI: It took four to five years to really get the hang of it. It is important to accept modern technology while still protecting tradition. If you just reject it, there’s no advancement. Progress through innovation is important. I don’t insist on state-ofthe art style, but we have to accept both new and old if they are good. For example, a gun is stronger than a sword, but it is useless without bullets. So a bayonet was invented. We should protect tradition, but at the same time we should be willing to alter it. If not, we can’t make progress. On the other hand, change without acknowledging tradition is completely wrong. Even if you use vivid colors, you can still keep Japanese traditional design alive. The present is based on the past, and the future is based on the present. We can’t deny the past.

TJ: What do you think of the Japanese mentoring relationship?

TJ: What do you think of the Japanese mentoring relationship?

HORIYOSHI: For foreigners, the Bushido/ Samurai spirit would be easiest to understand. Samurai retainers should unconditionally obey the orders of a lord. Retainers swear allegiance to a lord, while a lord does his best for his retainers. Betrayal never exists between them. We can’t choose our parents when we are born, but we can choose our own mentor. On the day I became Horiyoshi’s pupil I was introduced to a small room where I’d be living. At that time, I decided to dedicate myself to him. The relationship between a mentor and pupil is based on that kind of concern for each other. Not only interests and skills, but mind and body should be devoted to each other as well. I once said I could do anything, even killing others, for Horiyoshi. It is extreme, but the relationship is that strong. After Horiyoshi I died I decided to take care of his daughter and wife for the rest of my life. He mentored me, so I had an obligation to repay.

TJ: Do you think Irezumi will ever be accepted in Japan?

TJ: Do you think Irezumi will ever be accepted in Japan?

HORIYOSHI: It is difficult to answer. Last year, a Maori woman with Irezumi was rejected from a Japanese spa. At the upcoming 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, many athletes and visitors with Irezumi will attend. I think attitudes in the government will determine the future. Frankly speaking, I don’t have much hope. I’m not sure how Irezumi will be treated in the future in Japan.

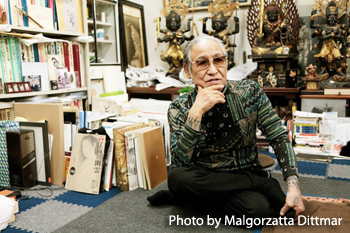

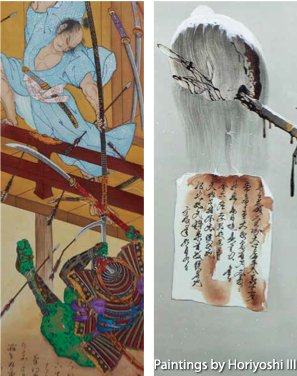

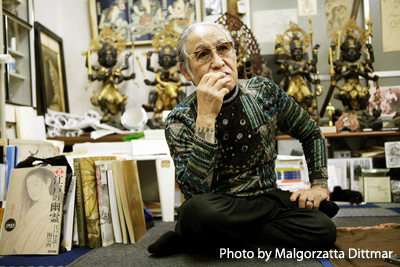

TJ: What inspires your artwork?

HORIYOSHI: Everything in daily life. For example, pictures uploaded to Instagram or Facebook are wonderful sources. Everything around me stimulates my imagination. Imagination depends on the amount of knowledge you acquire. You can’t imagine what you don’t know. Therefore, you have to obtain knowledge in day-to-day life.

TJ: Which artists have influenced you?

HORIYOSHI: I was affected by Hokusai the most, followed by Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Kyosai, Yoshitsuya, and Kuniteru, the Utagawa family... Michelangelo, da Vinci, Raffaello and other Renaissance painters. Everything in the world of art affects me without restrictions.

TJ: Which tattoo artists do you admire?

HORIYOSHI: I admire Ed Hardy the most because of his personality and depth of knowledge. He is a true gentleman. I feel close to Bob Roberts because he was born on the same day as me and had some similarities growing up. I have a lot of other favorite tattooists.

TJ: What is most important to you as a tattoo artist?

HORIYOSHI: An inquiring mind is most important. Jealousy is the worst. You should make efforts to surpass your rivals instead of feeling jealous. If you keep up the effort, you will succeed for sure. You have to gain experiences. You have to be hungry, absorb things. Jealousy shorts out your creativity.

TJ: What are the biggest challenges for a tattoo artist?

HORIYOSHI: Maintaining a good relationship with others, improving your skills, selfcontrol. You have to overcome the internal struggles. I am proud that I can keep doing it. I have confidence to keep doing it in the future, and I think I have to make more efforts. Also, I am proud that I can pour my energy into other things than Irezumi such as scroll paintings.

TJ: Have you ever tattooed celebrities?

HORIYOSHI: Yes, I have, but I can’t say their names.

TJ: Any future projects or goals?

HORIYOSHI: As for projects, nothing special. I’m pretty spontaneous. But I want to be ready for any occasion. We are all mortals. My last goal is to die well. To die well means to have lived well. I want people to regret my death. I don’t want a funeral service because I don’t want to leave my family that responsibility. I want to die beautifully. tj

The original article can be found in Issue #274 of the Tokyo Journal. Click here to order from Amazon.